An archive of articles on the silent era of world cinema.

Copyright © 1999-2025 by Carl Bennett and the Silent Era Company.

All Rights Reserved.

|

|

The Garden of Shadows

(Laemmle Film)

BY GRACE OPPEN

WRITTEN BY OLGA PRINTZLAU CLARK PRODUCED BY LUCIUS HENDERSON

Cast of Characters:

The Mother . . . . . . . . . Mary Fuller The Father . . . . . . . . . . . . . Niles Welsh

The Child . . . . . . . . . . Violet Axtell

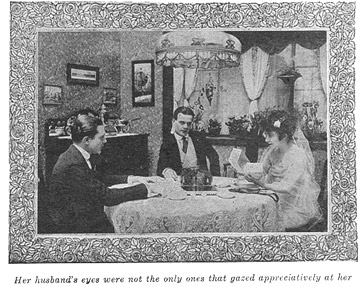

“AND now for the anniversary gift!” laughed Florence, when the deft maid had removed the dessert plates and left them to linger over their after-dinner coffee. “It certainly isn’t very heavy, dear,” weighing in her hand, the white paper carton her husband has just given her. “You haven’t been foolish again, and squandered your substance on another diamond, I hope, you dear, extravagant boy?”

Her young husband gazed across the table at her mute worship in his eyes. Never had she looked lovelier or more desireable to him than now, as she sat examining the mysterious package, her shining head tilted a bit to one side in whimsical curiosity, her sensitive lips pursed up in an adorable, childlike little pout. She had been so much of a child when he had married her, five years before — and she was still such a child! Romantic, irresponsible, beautiful — real life, with its cares and its stern lessons had hardly touched her. She was like a lovely hothouse flower whose tender beauty was its only excuse for being.

“You said last Christmas that you didn’t care about any more jewels, Florence, and I couldn’t think of anything else that you didn’t have already. The little thing in that box has absolutely no intrinsic value, but I think you will like it all the better for that. I wanted to prove to you that I’m not really quite so bad as you think, and that I’m not always thinking of money, and the things that money can buy.”

There was a wistful shadow in his adoring, boyish eyes as he spoke. In spite of five years of married life, in spite of the little daughter who had come to them, he and Florence still seemed to be divided by a shadowy something that he could not quite analyze. He felt himself vaguely to blame, and told himself that she was too good for him or any man — that Florence’s soul was too fine and delicate for every-day life.

Florence herself would have been the first to agree with him had he been able to put his vague feeling into words. She was discontented with life, because it was disappointing and “so terribly material,” as she was wont to complain. The truth was, it was disappointing because it was so empty and idle, because she floated in clouds of romantic fancy when she ought to have had her feet on solid earth, ministering to the needs of the man who loved her, and the little child who has been from the first in the care of a paid nurse. In all her care-free young life, Florence Evans had never known the chastening touch of a real sorrow, and the result was that she had never really grown up; she was just the beautiful, spoiled child her husband has fallen in love with and married five years before — dreamy, romantic, longing for an unutterable something that she had not yet found. Florence herself would have been the first to agree with him had he been able to put his vague feeling into words. She was discontented with life, because it was disappointing and “so terribly material,” as she was wont to complain. The truth was, it was disappointing because it was so empty and idle, because she floated in clouds of romantic fancy when she ought to have had her feet on solid earth, ministering to the needs of the man who loved her, and the little child who has been from the first in the care of a paid nurse. In all her care-free young life, Florence Evans had never known the chastening touch of a real sorrow, and the result was that she had never really grown up; she was just the beautiful, spoiled child her husband has fallen in love with and married five years before — dreamy, romantic, longing for an unutterable something that she had not yet found.

Her husband’s eyes were not the only ones that gazed appreciatively at her as she gingerly opened the carefully wrapped box. Eustace Norton, her husband’s college chum, had been invited to partake of the little anniversary dinner, and he too admired her fresh loveliness, as she sat at the head of her perfectly appointed table, swathed in a snowy cloud of silk and tulle. She looked more like a bride of to-day, he reflected, than a wife of several years’ standing.

“Oh! It’s perfectly wonderful! It’s the nicest thing you’ve ever given me, Tom!” There was genuine delight in Florence’s eyes as she looked at her gift, lying white and pure in its nest of green leaves. A single white rose, cool and lovely in its dewy freshness, was the husband’s token. It carried a subtle message that they both understood, and Eustace Norton, intercepting the look that passed between them at the moment, felt that after all there were some streaks of unsuspected imagination in old Tom, lost in business and matter-of-fact though he ordinarily seemed. “A white rose!” thought Eustace scornfully. “That’s a very pretty matter of sentiment, but I should have chosen red ones — roses — that’s what she’s made for. And Tom doesn’t realize it. He thinks his quiet, steady, respectful devotion and white roses are what she wants. So does she, because she doesn’t know anything else yet. But passionate, red, red roses — roses with hearts of glowing fire — those are what I should give her. That cold, white flower is more fit for the dead than for an eager, living, palpitating woman!”

Florence, however, was more than pleased with her single white blossom. She darted impulsively over to her husband’s chair and hung over him affectionately, just brushing her soft, flushed cheek against his lean, sunburned face.

“I shall keep it always, dear,” she said softly. “And I’ll forgive you for thinking of business most of the time, the way you do, if you’ll only think up something as nice again, soon.”

But expressions of sentiment did not come easily to Tom’s blunt, honest nature. His love for his romantic, young wife was like the still waters that run very deep. He had a feeling that the test of true love is the number of things one can leave unsaid and take for granted, assured of a wordless understanding. And so, during the months that followed, Florence found in his silent affection no repetitions of the flash of the romantic play which her nature craved. Life went along at a comfortable jog-trot, and she sought in card parties and theatres and dances the excitement she demanded.

One new element of interest, however, had been added since the evening of her anniversary dinner. Red roses — beautiful, glowing blossoms with hearts of fire — had kept arriving at her home, addressed to her, but with no indication of where they came from or why they came. At first she had suspected her husband of this new way of trying to please her, but his solid, matter-of-fact attitude toward the presence of the flowers soon convinced her that he had nothing to do with the matter. It must be some one else — some one who understood her, and whose soul was attuned to her own, above the sordid round of every-day life. She said nothing to Tom, and silently went over the list of her acquaintances. There were two of three who might be capable of the thought. Which one was it?

The secret excitement of the question began to absorb more and more of her interest, and gradually she because almost certain of the identity of the donor. Eustace Norton’s outer attitude toward his friend’s wife was all that convention demanded. He said nothing, did nothing that Tom could possibly have objected to. In fact, Tom often asked him to escort Florence here or there when the exigencies of business kept him away from home, and on these occasions even Florence could not have put her finger on any definite act or word that would mark him as the secret admirer who was content to express his hidden devotion by lavish supplies of roses — red, red roses. But there was an undercurrent of tremulous emotion in their intercourse which made Florence sure that here at last she had found a kindred spirit.

One night, when Tom was away on one of the frequent business trips which so annoyed Florence, she received a telephone message from Eustace, asking her to go to the theatre with him that evening. She accepted hesitantly — this was the first time that he had ever acted on his own initiative in such a matter, without a request from Tom, and she felt instinctively that matters were coming to a crisis.

She arrayed herself with unusual care in soft, black lace gown without a touch of color — except the flaming bunch of red roses she wore at her breast. They had arrived from the unknown sender that afternoon, and never had she seen more beautiful blossoms. She upbraided herself as she pinned the crimson beauties to her corsage, but the temptation to wear them was irresistible. She must find out definitely whether or not Eustace was the donor. A few hours later she and Eustace returned home, and the secret was not yet out. They entered the shadowy drawing-room, and stood silent for a few moments at one of the great windows, looking out into the moonlit garden. The sensuous music of the closing act of the play still filled Florence’s ears, and for some reason she did not feel like switching on the electric light or talking. She fingered her great bouquet of rose silently, and mechanically unpinned them and held them to her burning face.

“Of course you know where they came from, dear —” Eustace’s voice was at her ear, and it held a curious deep note that was thrilling and unmistakable in it significance. He stood so near that the breath stirred her hair, and the closeness of his presence seemed to envelop her. She looked up into his face with startled surprise at the suddenness of the question and the unexpected flood of emotion which was mastering her.

“Did — did you send them?” she faltered helplessly.

“You know I sent them; you know I’ve been sending them these many months — red roses to carry the message I dared not put into words. You knew it all the time, didn’t you, Florence?”

“Yes,” she breathed softly, “I knew it all the time. I tried to make myself believe that I didn’t know, because I didn’t want to stop their coming. They were like a message of beauty and romance from some one who understood how lonely I was.”

“I know, sweet, I know,” said Eustace softly. “Tom’s mind is so taken up with what he calls practical matters that he forgets the roses of life. I wanted to supply them.”

His arm stole around her waist, and she swayed toward him. They belonged together, she dimly told herself. Here at last was the sympathy and understanding she had always longed for and had never found.

A savage, inarticulate groan from among the shadows of the room startled them, and a brilliant flash of light from the electroliers half blinded them as some one ruthlessly turned on the lights.

“Florence! You!” Tom’s face, distorted with pain and rage, confronted them with livid accusation. The shaft of jealousy has struck into Tom’s heart with devastating cruelty, and he was speechless with the hurt of it all.

The three stood silent — the accusing and the accused. There was little to say. The situation when Tom switched on the lights was apparent. Florence tried to speak — tried to tell him that things were not so bad as he imaginated — but her throat closed up and she could only hang her head piteously. Eustace, cool and calm, for reasons of his own, offered no defense.

Tom’s ashen face worked convulsively, and then suddenly, losing all control, it broke. He turned from them and buried his face in his hands. Only the shudder of his shoulders under the dry sobs he strove in vain to repress told of his agony. No words of accusations, no storm of abuse, could have made Florence feel more guilty. She felt like the unintentional murderer of some innocent thing, and motioned Eustace to leave the room.

When they were alone, she went hesitatingly toward her husband, intending to tell him that matters were not as bad as he suspected and to ask him to forgive her.

But Tom pushed her back and would not listen to her. He rushed from the room and locked himself into his den. When she followed him, he refused to open the door.

Next morning, after passing a sleepless night, Florence found a brief note, telling her that Tom had left her, and that if she loved Eustace he would not stand in her way.

“I love you too much, my wife, to want to keep you against your will,” the note read. “No other man can care for you as I have. But it’s not my way to cringe and whine in a case like this. You can get a divorce and marry him when the year is up. Till then, I’ll keep out of the way. You can draw on the bank as usual for what you may need.”

For several weeks that followed Florence was entirely alone. She refused all social engagements, and made excuses for her husband’s absence to her friends. Eustace was clever enough to keep away while the tragedy of her husband’s pain was still fresh in Florence’s mind. But every day there came the silent reminders of his surging, restless passion — red roses; the sweetest and most fragrant that the market could produce — great, dewy armful of them every day, some full-blown, some softly budding, but all carrying the message of romance and sympathy she longed for.

One day, as she was dressing in her boudoir, the maid brought her the usual long box of flaming blossoms, but this time there was a note which nestled among them.

“I have waited long and patiently,” it read. “Every day has been as eternity. I can wait no longer. May I come to see you to-night? I am waiting at your door for my answer. Let it be a kind one.”

Florence read the message in a daze. The time for romancing and drifting was past. She must make her decision, now and forever. She knew that is she allowed Eustace to call there could be but one outcome. Tom’s face, shadowy and pained, floated vaguely before her.

She took out her jewel case, and opened it with trembling fingers. A little, worn box was the thing she sought. It contained a dry, brownish flower that had once been a soft, white flower of fragile purity. She held it in her hand thoughtfully. It had been very precious to her, this rare token of her husband’s affection. Then she buried her face in the living, glowing profusion of crimson roses which Eustace had sent.

Suddenly she sat up straight, crushed the rose in her hand, flung it from her, and faced the maid with a haggard countenance.

“Tell him that he may come tonight,” she said.

That evening, she sat in the music room long before the appointed time, awaiting his coming. Her hands glided softly over the keys, and as she played she sang dreamily the words of an old Scotch song —

“My love is like a red, red rose

That’s newly blown in June —”

Gradually she became aware of a presence behind her. Eustace was leaning over her, murmuring hot words of love. He took her into his arms, and their lips met.

The next moment she pushed him from her and made her way to the open window. An overpowering faintness was gaining control of her, and she breathed the fresh air as a drowning man clutches at a lifebuoy.

A sweet little voice in the darkness outside called her name with childish eagerness, and, leaning out, Florence saw, standing there in the shadowy garden, a little white figure, barefooted and bareheaded.

“Mother!” the child called once more, eagerly, sweetly, with plaintive shyness. And in her baby hands, she extended to her mother a full-blown white rose, picked from one of the garden bushes.

“My baby — my own little baby!” Never before had Florence’s voice held that mother-tone. Never had she snatches up the baby with such fervent care, as she hastened her child to the little white bed from which it had escaped while the nurse had dozed.

Eustace watched for her return in vain, and at last, convinced that she would not, he left the house.

Meanwhile Florence bent over her little girl in an abandonment of grief and remorse. The tot had come to her, like a messenger from heaven, to remind her of her duty.

“What made you steal away into the garden, dear?” she questioned the little girl.

“I thought I saw Daddy standing there, and he looked lonesome. But when I get there Daddy wasn’t there. And then I called you, and you came and got me. I like to have you put me to bed, mother. Nurse is so rough, but you’re so soft and nice. Will you put me to bed to-morrow?”

“To-morrow, and the day after, and every, every day till you’re big enough to go to bed all by yourself!” came the response.

And little Florrie wondered why her mother cried, when she seemed so happy.

A week later, Florence and Tom stood together, arm in arm, above the sleeping child. Florence’s head was resting in happy abandonment on her husband’s shoulder. He stooped and kissed her tenderly.

“I was living in a garden of shadows, Tom, and our little girl came to me at the crisis and called me back to real life. I’m going to try to keep my feet on the ground after this, and do a woman’s work in the world. Love and service — those two things go hand in hand; don’t they, dear? I used to be willing enough to take the love, but I never thought about giving the service. Can you ever forgive me, Tom, for those wasted five years?”

For an answer, he kissed her. This article originally appeared in Moving Picture Stories, July 28, 1916, Volume VIII, Number 187, pages 1-5. The Progressive Silent Film List : The Garden of Shadows (1916)

|